Nirvana in Bloom

Nirvana’s Nevermind was released on September 24, 1991, with Kurt Cobain reportedly hoping to sell around 300,000 copies—a high watermark for artistically credible, relatively underground indie bands like his idols and label mates, Sonic Youth.

Only a few short months later, it knocked Michael Jackson’s Dangerous from the #1 slot on the U.S. Billboard charts and almost just as swiftly rendered hair metal and other bland pop acts obsolete, all the while ushering in an era of more authentic, raw-sounding indie rock.

The punk rock shot heard around the world.

It could be argued that no band has ever set off a bigger seismic cultural shockwave in the U.S. since the Beatles arrived from the U.K. some 30 years beforehand. Even so, the Beatles, Elvis, Michael Jackson were all pop acts. Nirvana represented something much more significant, with Kurt Cobain representing the formerly nonexistent voice of new generation with something to say.

And while it sounded like pop, metal, and punk rock swaddled in production perfection, but it was anything but pretty. (article continued below)

Free-download my latest release, a cover of Nirvana's "About a Girl":

Where were you when you first heard Nirvana?

I was riding shotgun in the beater car of a girl I had a crush on, circa 1992. She was a little older than me, more experienced and definitely cooler. Out of my league, but I was still holding out hope. We were both film students working on a friend’s short and had music and art in common. She started playing me cassettes of all the new bands she was into, none of which I’d ever heard of at the time: Pearl Jam (meh), Primus (too weird), Soundgarden (bar band Led Zeppelin)…

Then she popped in Nevermind. I asked if we could play the whole thing straight through. I didn’t talk at all, I just wanted to listen. After she dropped me off, I went out and bought a copy right away.

That night, my two fellow oddball friends and I toked up and listened to the entire record in my apartment at full volume, prompting the elderly widow living directly below my flat to pound on my ceiling with a broom. I don’t think we said a word throughout. We were all punk rock misfits in a terrible “band” with no gigs and no bass player, and this is what we were trying to sound like. What we wished we could sound like. What we didn’t know was possible musically—and certainly impossible for us, given our collective lack of talent and ability.

But goddamn, it was what we were trying to express.

There’s no other way to say it than to say that the record sounded like my day, my life, how I was feeling—and everything I was feeling about my uncertain future. I’d spent the day with a girl I couldn’t have, which feels about as frustrating, confusing, and bittersweet as Nirvana sounded. I was about to graduate college, but hadn’t really experienced life much outside of Pennsylvania. I had no fancy family connections to speak of, a non-committal support system for my nascent acting career, and only vague plans of leveraging that into some sort of big break in New York.

At that time, I’d been living in a shabby apartment in so-called Gay Ghetto in Center City Philadelphia for the last two years. I’d known people who were either HIV positive or dying, both of which made me afraid of sex and a terrible hypochondriac. A few years before, I’d protested the Gulf War but had long since given up caring much about politics or changing the world. I felt powerless in the face of real life approaching fast, and to make it all worse, the music of the time was absolute shit.

To put it mildly, Nevermind hit me and my art-school friends like a ton of bricks. The rest of the world soon followed.

When socially conscious punk rock went supernova

I’ll go out on a limb by making the assertion that anyone who loves Nirvana loves them for the music and what they represented before they hit the cover of Rolling Stone, which by my recollection was that moment when they went from being our band to everyone’s band.

I wasn't sure how I felt about this when I saw it.

I still remember my initial reaction to that cover. It was actually well after they’d became international celebrities. I thought Kurt was trying a little too hard with the oversized sunglasses and CORPORATE MAGAZINES STILL SUCK T-shirt. None of that mattered, though—I’d always be a fan, even though the relationship between us and their music felt less personal with everyone else having jumped the bandwagon. Kurt was wise enough, and perhaps self-conscious enough, to address the haters in the article within:

“I don't blame the average seventeen-year-old punk-rock kid for calling me a sellout… I understand that. And maybe when they grow up a little bit, they'll realize there's more things to life than living out your rock ’n' roll identity so righteously.”

Not to speak for Kurt, but I like to think he wasn’t talking about the fame and money that were being thrown at the band. He was talking about what their music meant, and what it meant to kids like me who got it.

Art isn’t something that just reflect the times—it’s part of its context. It interacts with its time.

You have to realize that before Nevermind, most of us mainstream suburban white kids had never heard anything like it. Most of the records we’d listened to up to that point were quasi-Satanic, about chicks, or empty nonsense. We didn’t know what “grunge” was.

From the outset, Nirvana had transcended that term, which had been used well before they came along but was probably popularized by some hack PR person or journalist. For starters, Kurt’s lyrics were smart, sarcastic, and socially aware in a way we weren’t used to. Kurt didn’t pander. In fact, several songs were about his hatred of the sheep mentality (Sheep being Kurt’s original title for the record).

Other songs directly or indirectly touched on animal rights, drug abuse, self-hatred and self-deprecation, gun control, frat boy culture, sexual assault, conformity, homelessness, and the failure of the hippie movement and baby boomers in general—all arguably making the record more relevant than ever, if not timeless. These songs were not about “their dicks and having sex,” as he told PBS’s Blank on Blank in 1993.

"A vocal opponent of sexism, racism and homophobia, [Cobain] was publicly proud that Nirvana had played at a gay rights benefit, supporting No-on-Nine, in Oregon in 1992... Cobain was a vocal supporter of the pro-choice movement and Nirvana was involved in L7's Rock for Choice campaign. He received death threats from a small number of anti-abortion activists for participating in the pro-choice campaign, with one activist threatening to shoot Cobain as soon as he stepped on a stage." — Wikipedia

One thing that faded over time amidst the chaos of Nirvana’s popularity and celebrity was Kurt’s acerbic wit and sarcasm, which had nothing short of laugh-out-loud stopping power when I first listened to Nevermind (I personally found most of “Lithium” and the very beginning and “Duh” at the end of “Territorial Pissings” particularly hilarious). The cover of Nevermind itself was a clever misfit’s editorial cartoon of sorts that represented punk-rock Kurt’s conflicted feelings about “selling out” on a major label. But it was also about us: anyone who’s ever worked for someone else, the price of success (or shallow pursuit thereof), the human condition in general.

After they got huge, there were those funny, authentic, subversive on-camera moments, like Kurt showing up in a gown to MTV’s “Headbanger’s Ball” (confusing and frustrating the shit out of metal host Riki Rachtman); singing a horrible-sounding octave lower on their “Top of the Pops” appearance; Kurt deep-kissing Krist over the closing credits of their SNL appearance. The shock and awe have faded with time, but I still think the video for “In Bloom” is one the funniest and most clever I’ve ever seen.

Punk rock packaged for mass consumption

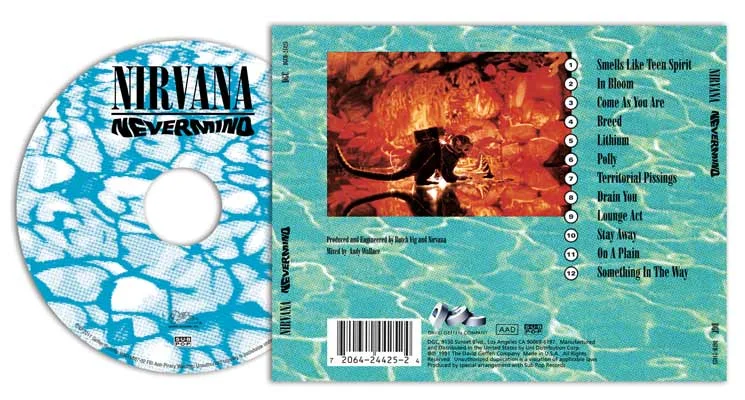

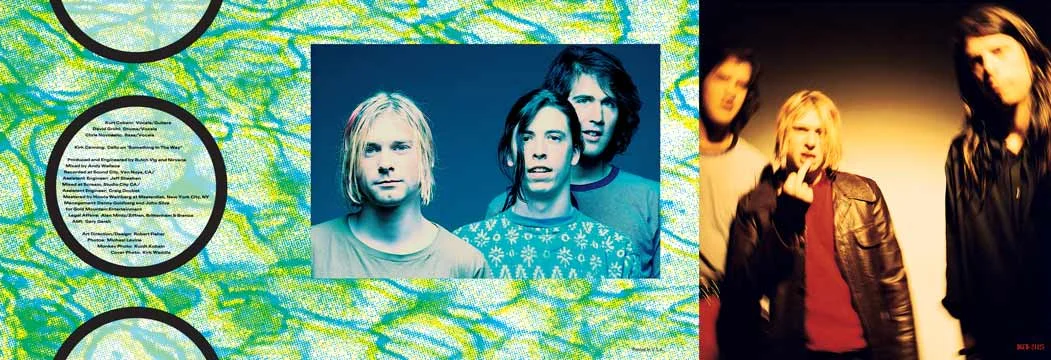

At that listening session with my bandmates, I remember turning the CD jacket for Nevermind over in my hands to study the three photos of the band and incomplete lyrics.

Wow, they look weird, I thought, but like average dudes (i.e. like me and my friends). In fact, they were sort of ugly—at least the photos made them look that way. The water theme was the perfect graphic design expression of the trippy chorus pedal on many of Kurt’s guitar tracks. And WTF is that on the back cover? A monkey on a jet pack? Haha! This is already way better than those Pearl Jam bros high-fiving on their cover.

The back cover of the album features a photograph of a rubber monkey in front of a collage created by Cobain. The collage features photos of raw beef from a supermarket advertisement, images from Dante's Inferno, and pictures of diseased vaginas from Cobain's collection of medical photos. Cobain noted, "If you look real close, there is a picture of Kiss in the back standing on a slab of beef.” — Wikipedia

The whole, disconcerting package perfectly captured the sheer raw power of the music, which ran the gamut from downright bizarre chord progressions to the saccharine-sugary power pop of their melodies and harmonies; from the incredible, propulsive power of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and “Territorial Pissings” to the quieter, dark art of “Polly” and “On a Plain.”

In short, the graphic design was the perfect visual embodiment of all the contradictions in the music itself—dark but poppy, chaotic but structured and polished, brutal and enigmatic, haunting and strangely accessible all at once. Contemporaries like Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, and Primus—and eventually Stone Temple Pilots, Everclear, and Alice in Chains—never came close to creating music that combined such multi-layered complexity with raw simplicity. I believe it was Chris Robinson from the Black Crowes who in one interview said simply and someone profoundly, “The guy just writes great fucking songs.”

There was something about the music that was so completely attuned to our wavelength that it sounded like they were performing for me and my friends right there in my shitty apartment. We would all eventually learn more about Kurt’s difficult upbringing as a child of divorce in Aberdeen, Washington—a depressed logging town with some of the highest suicide rates in the U.S. Like me, he hated sports, was bullied, and was into art and music. At the time of this first listen, I knew absolutely nothing about Kurt or the guys in this band. I just knew I connected with the music on some primitive, primordial level. It rocked and they sounded great, especially this guy’s voice and crazy guitar playing. Maybe just as importantly, I was fairly certain that like me, these three guys didn’t come from money, they were freaks, and they had something real to say.

The end of an era

After listening to Nevermind, I remember thinking if a band this good could get signed, I could at least try.

A few months later, about to graduate college, I started teaching myself guitar and, with about $40 to my name, moved to Pittsburgh to start my own rock band as a singer/songwriter/guitarist. I didn’t have Kurt’s talent, but with a lot of hard work, my new band the Movies was playing good clubs with good bands after just a few months. Fast forward a year, when we put out our first record (available on cassette only). I set the text on the cover in Onyx, just like Nirvana’s logo, above it’s title, Geeks and Gods, which was what a fan called Kurt after his suicide (“He was a geek and a god.”)

I will never forget where I was when it happened: my basement apartment, practicing guitar, when the phone rang.

“Did you hear?” It was my friend Sonia. “Cobain committed suicide.”

I know it sounds dramatic, but my world changed that day.

I knew something very special from a cultural standpoint had already been turning dark and ugly. In Utero was cool and all, but it sounded so bleak and brutal compared to Nevermind. (Kurt wanted to get his street cred back, so he had punk rock “recordist” Steve Albini produce.)

Any humor or irony from Nevermind morphed into something less impish and sarcastic into something more pissed off and mean. It seemed to go from a sly wink to some of us to a “fuck you” to all of us, including his wife. The record and everything going on in the media made it clear that Kurt was in a dark place, was married to a woman with questionable motives and values, was a drug addict, and had already survived a possible botched suicide attempt.

Part of me couldn’t believe he’d done that to himself. To us. To me.

It wasn’t like he clumsily drowned in a bathtub like Morrison or choked on his own vomit like Bon Scott. He’d deliberately and in the most violent way taken his own life.

A lot of what I was doing as a green musician and songwriter was inspired by what Kurt and Nirvana had achieved, and what they represented to me as artists. If someone wasn’t out there being the best at being different, then what else was there?

There was no one else to look up to the way I looked up to Nirvana. Sonia and I talked about one of my more recent “Nirvana moments,” when I heard a track from Nirvana Unplugged for the first time over the PA in a crowded bar. And again, just like I had so many years ago, time seemed to stand still.

What I’d heard that day sounded like the history of American rock music all wrapped up in one voice, one guitar, one song. I tried to place it, thinking at first it might be Tom Petty, but I soon learned it was Nirvana moving in the more Americana-acoustic direction Kurt could’ve taken his music for the rest of his life (Michael Stipe from R.E.M. has since confirmed he was on a path for doing exactly that). I felt a sense of relief and vindication on his behalf—for all Nirvana fans—that he’d gotten the grime out of his system and evolved his art again, just like he had over the course of four short records before Unplugged. And once again, it was transcendent.

Nirvana "Unplugged" was taped at Sony Music Studios in New York City on November 18, 1993. Kurt's suicide would be discovered a few short months later on April 8, 1994.

"Yeah, he talked a lot about what direction he was heading in", Cobain's friend, R.E.M.'s lead singer Michael Stipe, told Newsweek in 1994. "I mean, I know what the next Nirvana recording was going to sound like. It was going to be very quiet and acoustic, with lots of stringed instruments. It was going to be an amazing fucking record, and I'm a little bit angry at him for killing himself.”

My friend and I hung up and I remember wanting to cry a little. This was well before the days of social media grief porn, and I’m quite sure it was the first time I felt this way upon hearing a celebrity died. My hero was gone, and we knew enough about Kurt’s journey to know he’d lost something along the way as well.

When he was alive, after he got famous, Kurt would often help promote lesser known indie bands like Flipper and the Pixies while slamming contemporaries he didn’t respect and didn’t want to be associated with like Pearl Jam and the Lemonheads. The former is a given for anyone who’s been part of the punk/indie rock community, while the latter seemed more unique to Kurt—at least at the time, before the rise of social media amplifying musicians trashing their peers.

This kind of angry media snark on Kurt’s part could have been construed as some punk rock combination of artistic integrity and a competitive streak. But the more I learned about Kurt through his music, interviews, and books about Nirvana, the more I realized how image- and peer-conscious he really was, to a fault—to where the schism between how the world saw Nirvana and how Kurt saw himself made him miserable.

I still can’t believe trolls have the capacity to trash a tragic figure like Kurt Cobain, to call him a coward and a weak piece of shit for being an addict and all that. The lack of compassion and empathy for someone in that much pain—whether it’s mental, physical, or both—still leaves me dumbfounded. It goes against the all the feeling, awareness, and sensitivity Kurt expressed in his music, however acidic it may seem to those who don’t know any better.

Kurt’s may be gone, but rock will never die

More recent events like Tom Petty’s recent passing, Guns ’n’ Roses doing a nostalgia tour, the Kardashians wearing Metallica T-shirts, Gene Simmons declaring that rock is dead, and guitar sales being in steep decline make me deeply concerned about the present and future of rock music.

In making a big point of trashing lesser bands while promoting ones no one had ever heard of, maybe Kurt was on to something—self-consciousness and insecurities aside—in terms of making sure Nirvana was never overly concerned about pleasing everyone. Kurt said himself in his suicide note:

“All the warnings from the punk rock 101 courses over the years, since my first introduction to the, shall we say, ethics involved with independence and the embracement of your community has proven to be very true. I haven't felt the excitement of listening to as well as creating music along with reading and writing for too many years now. I feel guilty beyond words about these things.”

There was something about Nirvana’s success that divided Kurt from how he saw himself and wanted to be seen. I highly doubt it’s the whole story of why someone would want to take their own life, but this was something that Kurt couldn’t deal with.

“He had the desperation, not the courage, to be himself,” said Dave Reed, who was Cobain's foster father for a short time. “Once you do that, you can't go wrong, because you can't make any mistakes when people love you for being yourself. But for Kurt, it didn't matter that other people loved him; he simply didn't love himself enough”

Nirvana’s timeless legacy

Is Nirvana still relevant today?

I do know that kids picking up instruments without formal training to play rock music always will be—especially when it comes out sounding like Nirvana did. Especially when it’s saying and expressing something meaningful along the way, whether it’s through the music, statements, or action.

Haters like Wayne Coyne from the Flaming Lips have ingeniously and unoriginally dissed Nevermind—publicly pissing on a dead man’s grave—then go on to cover Nirvana songs. To me it just underscores how Nirvana’s popularity and approach to making the record more accessible may have been more polarizing than the music itself. And how their legacy, in my view, will only grow over time, perhaps even more so in the digital age, with Nevermind having already become the third most streamed album ever.

But hey, enough musings from me… Let’s hear from the musicians I love, who loved Kurt and Nirvana:

“You know, the guy just wrote beautiful songs… When someone goes that honestly straight to the core of who they are, what they’re feeling, and was able to kind of put it out there, I don’t know, man, it’s amazing. I remember hearing it when Nevermind came out and just thinking, we’ve finally got our Beatles, this era finally got our Beatles, and ever since then it’s never happened again. That’s what’s interesting. I was always thinking maybe the next 10 years. OK, maybe the next 10 years, OK, maybe… That was truly the last rock ‘n’ roll revolution.”

— Billy Joe Armstrong, Green Day (Time Magazine)

"When Nevermind came out, my roommate had the CD. At first, I actually thought, 'This is too polished and commercial.' It was a little off-putting. But then I was like, 'This is the best music ever.' It felt so close to what I wanted to do. I thought, 'I can write chord progressions like that. I can write melodies like that. This is something I can do.' This was right around when Weezer started. I probably wrote 'The Sweater Song' and 'The World Has Turned and Left Me Here' and 'My Name is Jonas' that month—all those early Weezer songs—and then we had our first rehearsal in February of '92. It's impossible to avoid the conclusion that Nevermind really inspired us to go for it.”

— Rivers Cuomo, Rolling Stone

“I remember my friends telling me that Kurt had died. It was such a great blow—not only to me, but to everyone in Weezer. It was very hard to listen to any other music for weeks after that. Nothing sounded as sincere as Nirvana’s music. It took a long time for me to accept that any other music could be good in other ways. Including my own.”

— Rivers Cuomo, Weezer (Time Magazine)

“With Kurt Cobain you felt you were connecting to the real person, not to a perception of who he was—you were not connecting to an image or a manufactured cut-out. You felt that between you and him there was nothing—it was heart-to-heart. There are very few people who have that ability.”

— Lars Ulrich of Metallica (Blabbermouth.net)

“The legend isn’t simply going to be the way that he took his life; I believe it will always be the songs.”

— Chris Cornell, Soundgarden

If you love Nirvana, I’d be honored if you’d take a listen and free-download my recently released cover of Nirvana’s “About a Girl.” Enjoy, and thanks for reading.